Introduction to Trees

The tree is a very commonly encountered data shape that allows us to represent hierarchical relationships.

It turns out that many of the structures we encounter when writing software are hierarchical. For instance, every file and directory within a file system is “inside” one and only one parent directory, up to the root directory. In an HTML document, every tag is inside one and only one parent tag, up to the root (html) tag.

It also turns out that that we can use trees to implement useful data structures like maps, and to do fast searches. We will cover some of the many use cases for trees in this section, as well as exploring algorithms to traverse through trees.

Examples of trees

Tree data structures have many things in common with their botanical cousins. Both have a root, branches, and leaves. One difference is that we find it more intuitive to consider the root of a tree data structure to be at the “top”, for instance that the root of a file system is “above” its subdirectories.

Before we begin our study of tree data structures, let’s look at a few common examples.

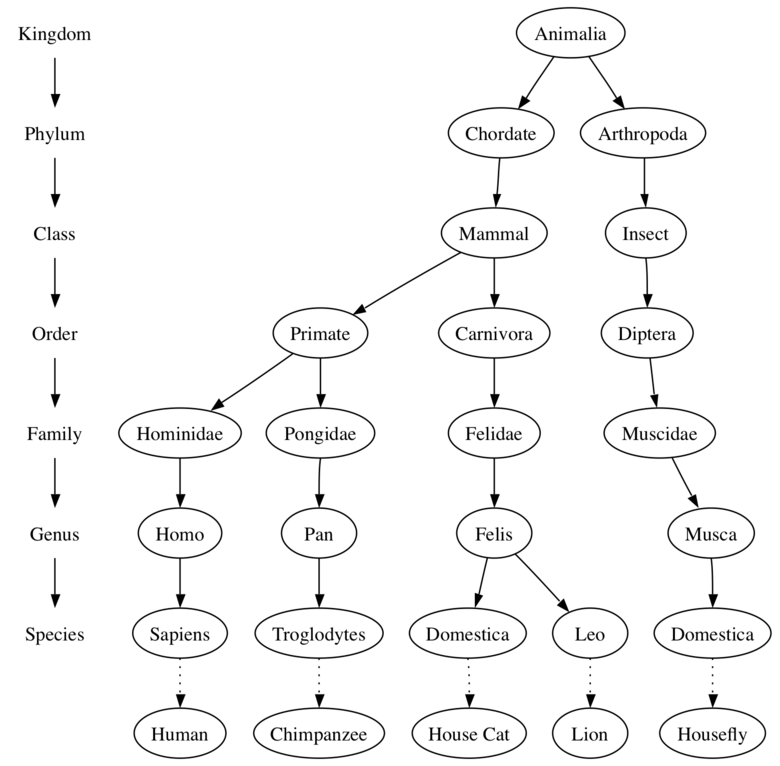

Our first example of a tree is a classification tree from biology. The illustration below shows an example of the biological classification of some animals. From this simple example, we can learn about several properties of trees. The first property this example demonstrates is that trees are hierarchical. By hierarchical, we mean that trees are structured in layers with the more general things near the top and the more specific things near the bottom. The top of the hierarchy is the Kingdom, the next layer of the tree (the “children” of the layer above) is the Phylum, then the Class, and so on. However, no matter how deep we go in the classification tree, all the organisms are still animals.

Notice that you can start at the top of the tree and follow a path made of circles and arrows all the way to the bottom. At each level of the tree we might ask ourselves a question and then follow the path that agrees with our answer. For example we might ask, “Is this animal a Chordate or an Arthropod?” If the answer is “Chordate” then we follow that path and ask, “Is this Chordate a Mammal?” If not, we are stuck (but only in this simplified example). When we are at the Mammal level we ask, “Is this Mammal a Primate or a Carnivore?” We can keep following paths until we get to the very bottom of the tree where we have the common name.

A second property of trees is that all of the children of one node are independent of the children of another node. For example, the Genus Felis has the children Domestica and Leo. The Genus Musca also has a child named Domestica, but it is a different node and is independent of the Domestica child of Felis. This means that we can change the node that is the child of Musca without affecting the child of Felis.

A third property is that each leaf node is unique. We can specify a path from the root of the tree to a leaf that uniquely identifies each species in the animal kingdom; for example, Animalia Chordate Mammal Carnivora Felidae Felis Domestica.

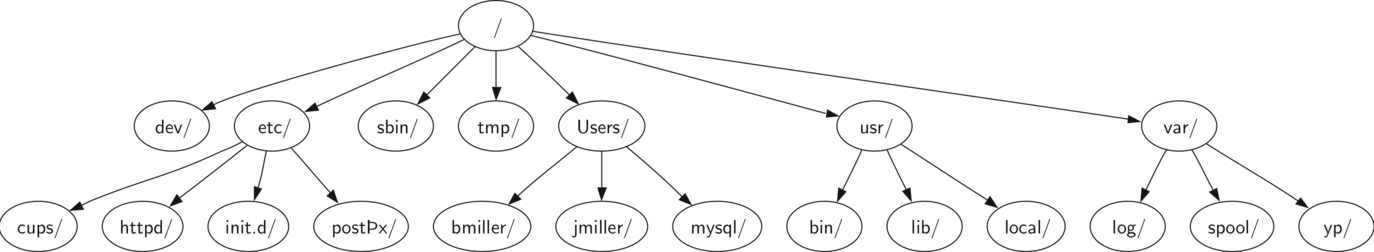

Another example of a tree structure that you probably use every day is a file system. In a file system, directories, or folders, are structured as a tree:

The file system tree has much in common with the biological classification tree. You can follow a path from the root to any directory. That path will uniquely identify that subdirectory (and all the files in it). Another important property of trees, derived from their hierarchical nature, is that you can move entire sections of a tree (called a subtree) to a different position in the tree without affecting the lower levels of the hierarchy. For example, we could take the entire subtree starting with /etc/, detach etc/ from the root and reattach it under usr/. This would change the unique pathname to httpd from /etc/httpd to /usr/etc/httpd, but would not affect the contents or any children of the httpd directory.

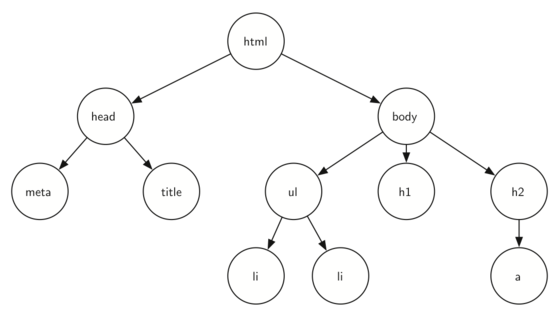

A final example of a tree is a web page. The following is an example of a simple web page written using HTML.

<html>

<head>

<title>simple</title>

</head>

<body>

<h1>A simple web page</h1>

<ul>

<li>List item one</li>

<li>List item two</li>

</ul>

<h2><a href="https://www.google.com">Google</a><h2>

</body>

</html>

Here is the tree that corresponds to each of the HTML tags used to create the page.

The HTML source code and the tree accompanying the source illustrate

another hierarchy. Notice that each level of the tree corresponds to a

level of nesting inside the HTML tags. The first tag in the source is

<html> and the last is </html> All the rest of the tags in the page

are inside the pair. If you check, you will see that this nesting

property is true at all levels of the tree.

Definitions

Now that we have looked at examples of trees, we will formally define a tree and its components.

Node

A node is a fundamental part of a tree. It can have a unique name, which we sometimes call the “key.” A node may also have additional information, which we refer to in this book as the “payload.” While the payload information is not central to many tree algorithms, it is often critical in applications that make use of trees.

Edge

An edge is another fundamental part of a tree. An edge connects two nodes to show that there is a relationship between them. Every node other than the root is connected by exactly one incoming edge from another node. Each node may have several outgoing edges.

Root

The root of the tree is the only node in the tree that has no incoming edges. In

a file system, / is the root of the tree. In an HTML document, the <html>

tag is the root of the tree.

Path

A path is an ordered list of nodes that are connected by edges. For example, is a path.

Children

The set of nodes that have incoming edges from the same node are said to be the children of that node. In our file system example, nodes log/, spool/, and yp/ are the children of node var/.

Parent

A node is the parent of all the nodes to which it connects with outgoing edges. In our file system example the node var/ is the parent of nodes log/, spool/, and yp/.

Sibling

Nodes in the tree that are children of the same parent are said to be siblings. The nodes etc/ and usr/ are siblings in the file system tree.

Subtree

A subtree is a set of nodes and edges comprised of a parent and all the descendants of that parent.

Leaf Node

A leaf node is a node that has no children. For example, Human and Chimpanzee are leaf nodes in our animal taxonomy example.

Level

The level of a node is the number of edges on the path from the root node to . For example, the level of the Felis node in our animal taxonomy example is five. By definition, the level of the root node is zero.

Height

The height of a tree is equal to the maximum level of any node in the tree. The height of the tree in our file system example is two.

With the basic vocabulary now defined, we can move on to two formal definitions of a tree: one involving nodes and edges, and the other a recursive definition.

Definition one: A tree consists of a set of nodes and a set of edges that connect pairs of nodes. A tree has the following properties:

- One node of the tree is designated as the root node.

- Every node , except the root node, is connected by an edge from exactly one other node , where is the parent of .

- A unique path traverses from the root to each node.

- If each node in the tree has a maximum of two children, we say that the tree is a binary tree.

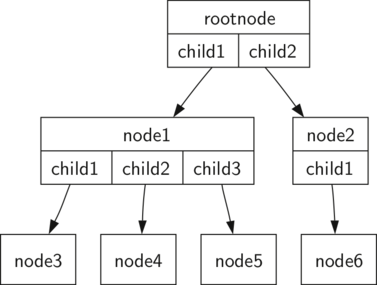

The diagram below illustrates a tree that fits definition one. The arrowheads on the edges indicate the direction of the connection.

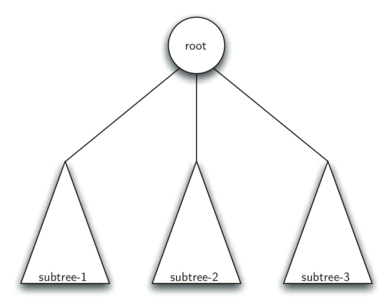

Definition two: A tree is either empty or consists of a root and zero or more subtrees, each of which is also a tree. The root of each subtree is connected to the root of the parent tree by an edge.

The diagram below illustrates this recursive definition of a tree. Using the recursive definition of a tree, we know that the tree below has at least four nodes, since each of the triangles representing a subtree must have a root. It may have many more nodes than that, but we do not know unless we look deeper into the tree.