Big O Notation

An algorithm is little more than a series of steps required to perform some task. If we treat each step as a basic unit of computation, then an algorithm’s execution time can be expressed as the number of steps required to solve the problem.

This abstraction is exactly what we need: it characterizes an algorithm’s efficiency in terms of execution time while remaining independent of any particular program or computer. Now we can take a closer look at those two summation algorithms we introduced last chapter.

Intuitively, we can see that the first algorithm (sum_of_n) is doing more work than the second (arithmetic_sum): some program steps are being repeated, and the program takes even longer if we increase the value of n. But we need to be more precise.

The most expensive unit of computation in sum_of_n is variable assignment. If we counted the number of assignment statements, we would have a worthy approximation of the algorithm's execution time: there's an initial assignment statement (total = 0) that is performed only once, followed by a loop that executes the loop body (total += i) n times.

We can denote this more succinctly with function , where .

The parameter is often referred to as the “size of the problem”, so we can read this as “ is the time it takes to solve a problem of size , namely 1 + steps.”

For our summation functions, it makes sense to use the number of terms being summed to denote the size of the problem. Then, we can say that “The sum of the first 100,000 integers is a bigger instance of the summation problem than the sum of the first 1,000 integers.”

Based on that claim, it seems reasonable that the time required to solve the larger case would be greater than for the smaller case. “Seems reasonable” isn’t quite good enough, though; we need to prove that the algorithm’s execution time depends on the size of the problem.

To do this, we’re going to stop worrying about the exact number of operations an algorithm performs and determine the dominant part of the function. We can do this because, as the problem gets larger, some portion of the function tends to overpower the rest; it’s this dominant portion that is ultimately most helpful for algorithm comparisons.

The order of magnitude function describes the part of that increases fastest as the value of increases. “Order of magnitude function” is a bit of a mouthful, though, so we call it big O. We write it as , where is the dominant part of the original . This is called “Big O notation” and provides a useful approximation for the actual number of steps in a computation.

In the above example, we saw that . As gets larger, the constant 1 will become less significant to the final result. If we are simply looking for an approximation of , then we can drop the 1 and say that the running time is .

Let’s be clear, though: the 1 is important to and can only be safely ignored when we are looking for an approximation of .

As another example, suppose that the exact number of steps in some algorithm is . When is small (1 or 2), the constant 1005 seems to be the dominant part of the function. However, as gets larger, the term becomes enormous, dwarfing the other two terms in its contribution to the final result.

Again, for an approximation of at large values of , we can focus on and ignore the other terms. Similarly, the coefficient becomes insignificant as gets larger. We would then say that the function has an order of magnitude ; more simply, the function is .

Although we don’t see this in the summation example, sometimes the performance of an algorithm depends on the problem’s exact data values rather than its size. For these kinds of algorithms, we need to characterize their performances as worst case, best case, or average case.

The worst case performance refers to a particular data set where the algorithm performs especially poorly, while the best case performance refers to a data set that the algorithm can process extremely fast. The average case, as you can probably infer, performs somewhere in between these two extremes. Understanding these distinctions can help prevent any one particular case from misleading us.

There are several common order of magnitude functions that will frequently appear as you study algorithms. These functions are listed below from lowest order of magnitude to highest. Knowing these goes a long way toward recognizing them in your own code.

| f(n) | Name |

|---|---|

| Constant | |

| Logarithmic | |

| Linear | |

| Log Linear | |

| Quadratic | |

| Cubic | |

| Exponential |

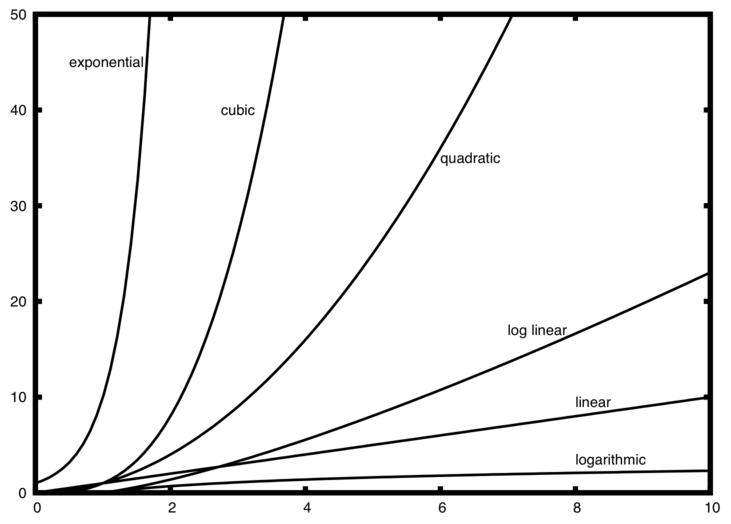

In order to decide which of these functions dominates a function, we must see how it compares with the others as becomes larger. We’ve taken the liberty of graphing these functions together below.

Notice that, when is small, the functions inhabit a similar area; it’s hard to tell which is dominant. However, as grows, they branch, making it easy for us to distinguish them.

As a final example, suppose that we have the fragment of Python code shown below. Although this program does nothing useful, it’s instructive to see how we can take actual code and analyze its performance.

a = 5

b = 6

c = 10

for i in range(n):

for j in range(n):

x = i * i

y = j * j

z = i * j

for k in range(n):

w = a * k + 45

v = b * b

d = 33

To calculate for this fragment, we need to count the assignment operations, which is easier if we group them logically.

The first group consists of three assignment statements, giving us the term 3. The second group consists of three assignments in the nested iteration: . The third group has two assignments iterated times: . The fourth “group” is the last assignment statement, which is just the constant 1.

Putting those all together: . By looking at the exponents, we can see that the term will be dominant, so this fragment of code is . Remember that we can safely ignore all the terms and coefficients as grows larger.

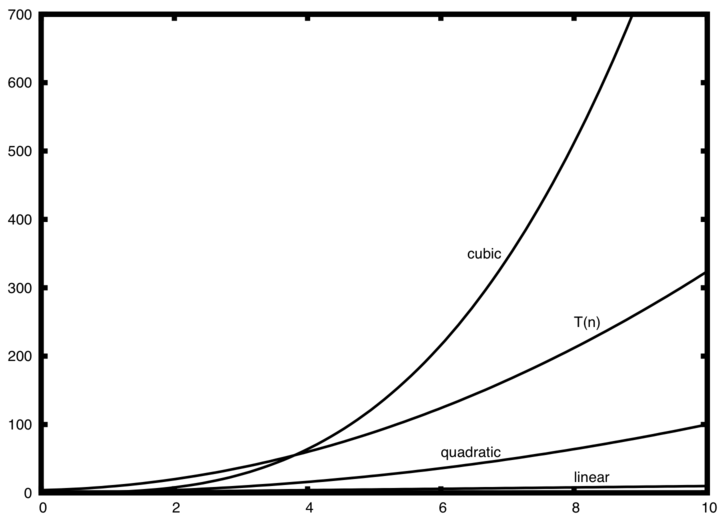

The diagram below shows a few of the common big O functions as they compare with the function discussed above.

Note that is initially larger than the cubic function but, as grows, cannot compete with the rapid growth of the cubic function. Instead, it heads in the same direction as the quadratic function as continues to grow.